Disclaimer

This is a work of fiction.

While the events, places, historical contexts, and cultural references depicted here are anchored in real histories, they have been fictitiously reimagined for the purposes of storytelling. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental or used solely as a point of artistic inspiration.

Some characters, scenes, and moments may evoke figures, icons, or historical events rooted in truth. However, the author intends these not as factual retellings, but as poetic representations, symbolic renderings shaped by imagination, personal narrative, and literary exploration. This is not a documentary account. This is a story.

Where history ends, fiction begins.

✩₊˚.⋆☾⋆⁺₊✧ Introductory Guide (Table of Contents, Blurb, and Characters) ✩₊˚.⋆☾⋆⁺₊✧

← Previous Chapter: [01: Ang Dilaw na Bestida (The Yellow Dress)]

→ Next Chapter: [Marina’s Archive 1]

1960s, Luz

EXT. PARLOR – 3AM, EARLY MORNING AFTER A GIG

When the night is neon, the darkness rebels against the saturation. It’s the kind of color you can feel on your palms.

Sweaty. Sticky. Grimy. Inelegant. The lick of amniotic fluid; God’s spit on hollowed land. The humming of beerhouses, the cheap motel signs blinking their slutty “VACANT,” the click-clack of heels on gravel roads, the stub of cigarettes glinting like cat eyes.

Everywhere is apocalypse.

Somewhere, under the vacuous ruins, beneath the tacky lights strung on a parlor sign, a baby cries. Not on a doorstep. Not on a cushion of trash. Not in a basket. This baby is left on a plastic monobloc chair outside Diding’s Beauty Emporium. The baby closes its eyes peacefully as she squirms beneath the peed-on 1lampin. It is embroidered with flowers, and the baby glows with the faint scent of Johnson’s Baby Powder—and, of course, city pollution.

A note is taped to her chest. It’s already wet, crumpled at the edges, and the ink is smudged like mascara streaks. “Love her like a true mother would.”

The street quiets. Against the drunk and the damp, the note feels harsh.

And then, the tinkle of laughter. Gigantic feet strutting. A key turning in a metal keyhole. Loud clang of a gate. Swivel of whispers. The owner of the parlor arrives first: Diding. Heels in one hand, wig in the other, and a steaming Styrofoam box of 2lugaw.

Behind her, the holy trinity: Charmaine, Tita Divine, and Pokpok. All three are loud like cymbals, music clattering into different notes as they gossip about boys, makeup, and their fellow 3kanal gays. Fresh from hosting a gay pageant, Diding laughs when they recount how a contestant threw a shoe at a judge for calling her “a man in a dress.”

The posse is exhausted. Eyeliner smudged. Stockings ripped. Their chaos is beautiful, a divine mosaic from the nightlife.

“Ay, puta,” Charmaine says, mid-yawn. “Why is there a baby here?!”

They all scream. They all pray. They all stare into the darkness, trying to see if the mother is still scurrying around. They scour through the world, searching for an answer to this baby sleeping so peacefully. They find none.

“Finally!” Diding whispers. “God has given us the fantasy of motherhood!” she jokes.

The night doesn’t laugh with her. The lights on the parlor sign blink like divine insight, a tarot reading. It says: Yes, this is your baby now.

And no one hesitates. Not even for a glittery second.

Divine scoops up the baby. She’s the better one. She once worked as a nurse. She’s always known how to hold something fragile. How to touch flesh with a maternal hand. How to tame a scream.

Pokpok coos, “Hija, welcome to the parlor of the sluts in this town!”

INT. SALON – YEARS LATER

The baby becomes Luz. Named after the pageantry of the word luxurious. They wanted Lux, but Diding sharply witted, “Cliché, darling.”

Pokpok pouted from the snippy shade, then snapped back an alternative, “Edi Luz!”

Everyone filed their nails, tasting the word on their tongues. It was acerbic sour like a cable drama, fiercely good-girl sweet like the tragic goody-two-shoes in teledramas. So they all screamed YES. And so the baby is birthed into a girl. LUZ.

She grows between mirrors sandwiched on the walls. When the silver images face each other, an infinite universe of Luz reflects her – weeping, snot on her nose, tears in her eyes, and always clothed in rainbow colors.

The mirrors in the parlor know how to recite her name like poetry. The mirrors never lie to her; they only reveal a future.

When the matriarchs of the parlor sit her down in the corner and do their magic on people—

those needing haircuts after a breakup,

an old neighbor nosing into gossip,

a woman with a black eye from her husband,

children who look at them like they are flesh-eating monsters.

The mirrors listen attentively.

To the gossip.

To the wives in long sleeves hiding crescent-shaped bruises.

To the husbands needing haircuts for their mistresses.

To the old folks seeking reprieve from their suffering, hoping a haircut might be the answer.

To the kids wanting to impress their friends.

To the closeted man preparing to look handsome for a secret sexcapade.

To the pastor who thinks it’s salvation.

To the nuns who believe long hair is a sin.

To the pageant girls needing a makeover.

And so much more.

The mirrors drink it all in while everyone bites their nails, hides their secrets, and wears their hearts openly. The mirrors tattoo the bruises, the powders, the silent reclamations happening while the scissors go snip snip snip.

As soon as Luz begins stifling her cries, grows out of pink lampins, and fills in the boldened body of a girl, she discards the sterilized milk and becomes twelve, with hair lush, healthy, and naturally brushed every night by her mothers.

Her skin is filled with anti-aging creams from her Nanay Diding. Her eyelids are colored neon by her Ate Pokpok. Her nails are polished, serrated, and painted through the craft of Charmaine. Her heart, full of love and sass, is taught by her Tita Divine:

“You’re young, but you need to learn now that someday, you will not stay a girl forever. You will become a woman. Maybe a mother. A prostitute. Or a reject. But one thing you will always have is your womanhood. ‘Kay?”

Luz nods.

At that age, she is already an expert at shampooing heads. She knows how to whisper the magic words, the therapeutic assurances, the agreeable statements to clients. She listens to heartbreaks and 4chismis. Her hands are growing into claws, but her touch is a mother cradling a child. The neighborhood knows the ridges of her fingers as they burrow into the scalps of the clients.

The 5barangay has dubbed her the healer of scalps.

Luz.

And at that tender age, she’s beginning to realize that people love silence from women. They expect it from them. She doesn’t speak much, but she also knows that her silence is not submission. It’s her way of studying. An absorption. Her silence watches how the parloristas live. Her silence offers an open ear to everyone’s darkness.

Her body sponges it all. Her silence is her company.

In the parlor, the memories are rich and always brimming.

Charmaine, in tears, recounts to the mothers how her lover left her again for a born-natural woman. She told him before she exited, “Hell is full of lipstick and semen, and you, a piece of shit!”

Tita Divine, who once showed Luz a secret tattoo on her inner thigh—one she got when she was a kid and her father drove them to the 6sabungan—that says: 7Barako Killer. She teaches Luz how to defend herself with just a makeup brush.

Her Ate Pokpok, who brings home different lovers every week, shushes her when Luz sees them. After, she gifts Luz a pancit and a sermon on how men are pigs.

Diding, her main mother, tells her 8kumares about her female impersonation performance in Olongapo to a bar full of American soldiers, exclaiming, “Believe me, boy-pussy is applauded!”

Luz loves them all. The parlor. The people. But especially, her mothers. Each of them queens—broken, crackled, shattered in different ways. Yet through the splinters is a beautiful light that keeps slipping through in glitter.

Luz never asks for her true mother. They are already enough.

When Diding asks her daughter about her disinterest in knowing her real parents, Luz only shrugs. “You are already enough, Mother.”

Diding cries at this, and still feels like she had stolen something.

“Sometimes, Mama,” Luz starts. Before she continues, she wipes Diding’s tears with the newly folded clothes on the bed. “True family is not by blood. Sometimes, a mother is someone who knows how to fold my panty while singing Kuh Ledesma.”

Against her ugly crying, Diding slaps her daughter’s shoulders jokingly. “You are full of jokes, 9anak, ha!”

INT. BATHROOM

When Luz turns seventeen, that ripe age turns her body inside out. It folds her into an origami of puberty. Breasts ballooning into sinful shapes. Waist wasping into a curvaceous shape. The puberty in her bones softens into womanhood. Her skin glows with desire. Every boy in town flits desiring gazes toward her when she works in the parlor. The mothers notice this flux of attention, and they make her more beautiful.

She was also seventeen when the existential crisis of a daughter rumbles in her chest. She realizes that she would never be a mother. She’s just not a mother. She can feel it in her marrow. She’s not a mother in the way women are told they must be. She tells this to her mothers, and they applaud her for the self-recognition.

“Correct! If you can’t be a mother, then don’t be, anak. A woman is not just a mother, hija! Motherhood is not for everyone.”

They scream all this placard wisdom to her with a fabulous flick.

Luz doesn’t need a husband. She has no path, but she has calluses on her hands and a childhood glossed with salon chemicals and secondhand glamour.

And through the cracks of the afternoon, fate giggles, as it has other plans for her.

“Luz,” Diding says, brushing her hair in front of the mirror, “if you have a son one day, and he’s gay, I will haunt you if you don’t love and protect him unconditionally.”

“I promise, Mama.” She carries the words in her palms, drinks them into her heart, and looks at her image in the reflection.

And there, she’s five again. She’s sitting on the spinning stool. Diding is brushing her hair like she always loved to do. The other mothers are laughing, sewing sequins into a gown for a pageant.

Diding kisses her forehead and says, “You are so beautiful, anak!”

Luz asks, “Really, Mama?”

Ate Pokpok answers her question, “Yes! Your face is like the Philippines. Everyone will fight for it!”

And against all her careful planning, her silent defiance of motherhood, her fierce ambition to build her own parlor one day with her own gay friends, everything will blur into Vaseline when she meets him.

INT. PARLOR – LATE AFTERNOON

The air inside the parlor smells of flowers, old fabrics, setting lotion, sweat, and hairspray. The oscillating fan rattles like a dying opera singer. The radio that Tita Divine clicks open hums another APO Hiking Society song.

Luz, with her hips swaying in bell bottoms, learned and practiced from the performance of her mothers, sweeps hair from the parlor floor. The bell on the door rings, and he enters.

The mothers swoon. They flap their wings. Everyone shimmers with awe. Luz drinks the image. Boots. Uniform. Soldier cut from a propaganda poster. The boy is sun-warmed and full of swagger. He isn’t wearing his camouflage jacket, so the muscle shirt exposes the dragon tattoo slithering on his body like a seductress owning him. He’s the kind of man who could eat the enemy.

His eyes devour every parlorista on shift. He doesn’t look at Luz.

“Good afternoon, sir,” Luz blushes and greets politely, hiding her nails behind her back.

The soldier finally looks at her. Everything glazes into a romantic slow-motion. The lens in his eyes becomes rose-tinted. He feels a rush under his skin, culminating in his chest, unfurling like a rose as he studies her. He takes off his cap and nods.

“They say this is the best parlor in Isabela,” he speaks in punctuated words, scanning the place. “The faggots from the camp recommend it greatly.”

The mothers toss away the slight twang of slur. They flurry toward him like peacocks. They all coo, “If the faggots say it like truth, then it’s the truth, sir!”

The room laughs flirtatiously. Luz blushes. She traces the scars on his knuckles with her eyes. Rough. Barbed-wire edgy. His neck.

When she walks past him to prop the 9walis tambo, she smells talc and musk. He’s handsome, but she also craves that danger lurking underneath his muscles. That afternoon, she ends up washing his hair.

His head rests in her hands. An offering. She could drink his lips. The water runs, and suddenly, when her fingers scrub through the oily scalp, the intimacy blooms like hot steam.

He asks softly. The thorns in his words fade into music. “Where are you from, pretty?”

“I was raised here. In the parlor with my mothers.”

He laughs. “They are your parents?”

She nods and corrects him, “My queens.”

He chuckles again, not even bothering to disguise the insult. “Queens?”

“Yes, sir. Faggots. Loudmouths. Rejects. Lovers. Fighters. Queens. They were crowned once as 10Miss Pangkalawakan.”

The laughter that escapes from his mouth is honest, a trace of his humanity against his armor of military. He opens his eyes and stares at her intensely. She braces for another ridicule, but he doesn’t speak, only looks into the inside of her soul like he wants to squeeze her insides and claim her.

A beat. The radio switches to Freddie Aguilar. Ironic.

A week later, the two are on a 11kanto date. They share fishballs and warm Coke from a straw.

The mothers wonder in the parlor. They share their syncopated kilig. They file their nails, they brush their wigs, they listen to the radio.

“Maybe the soldier likes her.”

“That girl is hard to win, Tita Divine, 12noh. She doesn’t want to be a mother!”

“Maybe, but love is full of possibilities!”

“Maybe?! So you think she likes him?”

“He is handsome, so yes!”

“Not every handsome face is a good man, ate!”

“True!”

In the plaza, she asks him, “Why are you here with me?”

He shrugs, and she can see the tautness of his muscles under the uniform.

“You look like the woman of my dreams.”

“What if I’m not that woman? What if I’m the woman of your nightmares?”

“Then let me be ruined.”

Luz laughs, but she can feel her heart galloping. The directness is rare. The honesty is intoxicating.

Everything becomes a whirlwind. She forgets her dreams. The pages of her ambition fly into a tornado. They become fire. They become smoke.

She is dragged out of the cocoon of her clean-cut path and into his world of soldiers, sirens, and sanitized masculinity.

He buys her bouquets, a cheap gold necklace, and takes her on dates every night. She wears the necklace until her skin becomes scaly green.

The mothers in the parlor watch her carefully.

The mothers should know they ought to watch the boy closer.

Some days, he goes to the parlor unannounced and brings her flowers from the camp.

The mothers wonder if the fauna there smells of death.

The first time he kisses her, she feels consumed.

When he’s drunk, he screams.

He’s intense and looks at her like he wants to tear her flesh.

He’s angry sometimes, but placated with sweetness.

The alcohol makes him a different person, but she likes his touch

.

INT. BOARDING HOUSE – NIGHT

When he proposes that they move in together, she doesn’t know how to say no.

The mothers in the parlor advise her not to. It’s too fast. She reasons that he’s being moved to another place. Tita Divine says it’s going to be a trap. Diding says it’s going to be hell for her. Ate Pokpok says she’s not meant to be a wife. Charmaine says their love is not secure.

But Luz is a stubborn daughter. They can’t always coddle her. Someday, she has to grow apart from them.

And she does.

She accepts his offer. They move in together. She discontinues her college education.

The mothers weep when she packs her bag. When they banshee-scream at her for being ungrateful, she slaps them with the truth that they are not her real mothers.

Ate Pokpok screams at her, “You will regret this! He’s not the man for you!”

She only screams back, “What do you know about love? You trash it so easily with the many men you sleep with!”

A heel flies at her before the door closes. It is exile.

They ride with the other soldiers. They move in together.

Fast. Foolish.

When they lie on the cheap mattress of their first apartment, he undresses her like she’s fragile. He holds her like a clean thing he hasn’t dirtied yet.

But soon, when he gets home drunk from training, the soft touches turn into shouting. Silence. Fury.

The nights she used to love with her mothers become jagged. Instead of brushing her beautiful hair in the mirror, she hides in the bathroom just to cry when she can’t cook his favorite meal right. She cries every night and prays to her mothers in Isabela to accept her again, to nurture her, to love her back.

The table screeches, the chair shrieks, the walls bleed, the bed squeaks. Everything sounds terrified when his boots stomp outside.

His presence has become a poison.

When he starts slurring in his drunkenness, he uses words like real family.

Luz asks herself if she’s ready.

In the mirror, she has become a husk of herself. All the flesh of love her mothers once filled in has turned into beaks of darkness.

“How could you raise a child when you were raised by trash?”

She feels anger, she feels defenseless, but she also feels the need to protect her mothers from the insult. So she says, “More than you know.”

And a slap.

She doesn’t cry.

When she kneads the bruise in the mirror later, she is reminded of her Mama Diding: “Queens don’t cry.”

When she gets pregnant, the apocalypse is just beginning.

As her stomach grows into a mountain, she whispers love to the child inside her. She promises a better future.

Against all the fists, the knuckled violence, the bulleted words, she will shield herself when it comes to this kid.

She will do what her mothers did to her: love unconditionally.

Against all anomalies, she will become a good mother.

So, when her son arrived with a body that is abused, scarred, wounded, pained, and hurt by the person who created it, a failure slinks inside her as a mother.

Now that Luz is a mother, she watches Marina sleep. Her daughter’s bruises are still fresh. Her body is wrapped in bandages. Luz knows how to translate it. She’s seen so many silences and ways of bleeding quietly.

She goes to the kitchen. She prepares the 13sopas with evaporada and hotdog bits. It’s what her Nanay Diding made for her when she first got her period. She thought it was death coming for her.

She spoons it gently into Marina’s lips. She moves her muscles like the way Charmaine once spoon-fed her when she had a fever one summer and no hospital wanted to accept them.

Her hands shake. She wipes the tears from Marina’s ducts just like how her Ate Pokpok did when she failed a quiz.

She closes her eyes and hears the metal of scissors, laughter, the radio ballads. They reverberate against the walls now. The salon wraps them in infinite mirrors.

She hears Tita Divine against the chismis, “I don’t want to prophesize that you will be a mother someday, but if he will turn out like us, naku, ready yourself for apocalypse. It will be so hard, anak.”

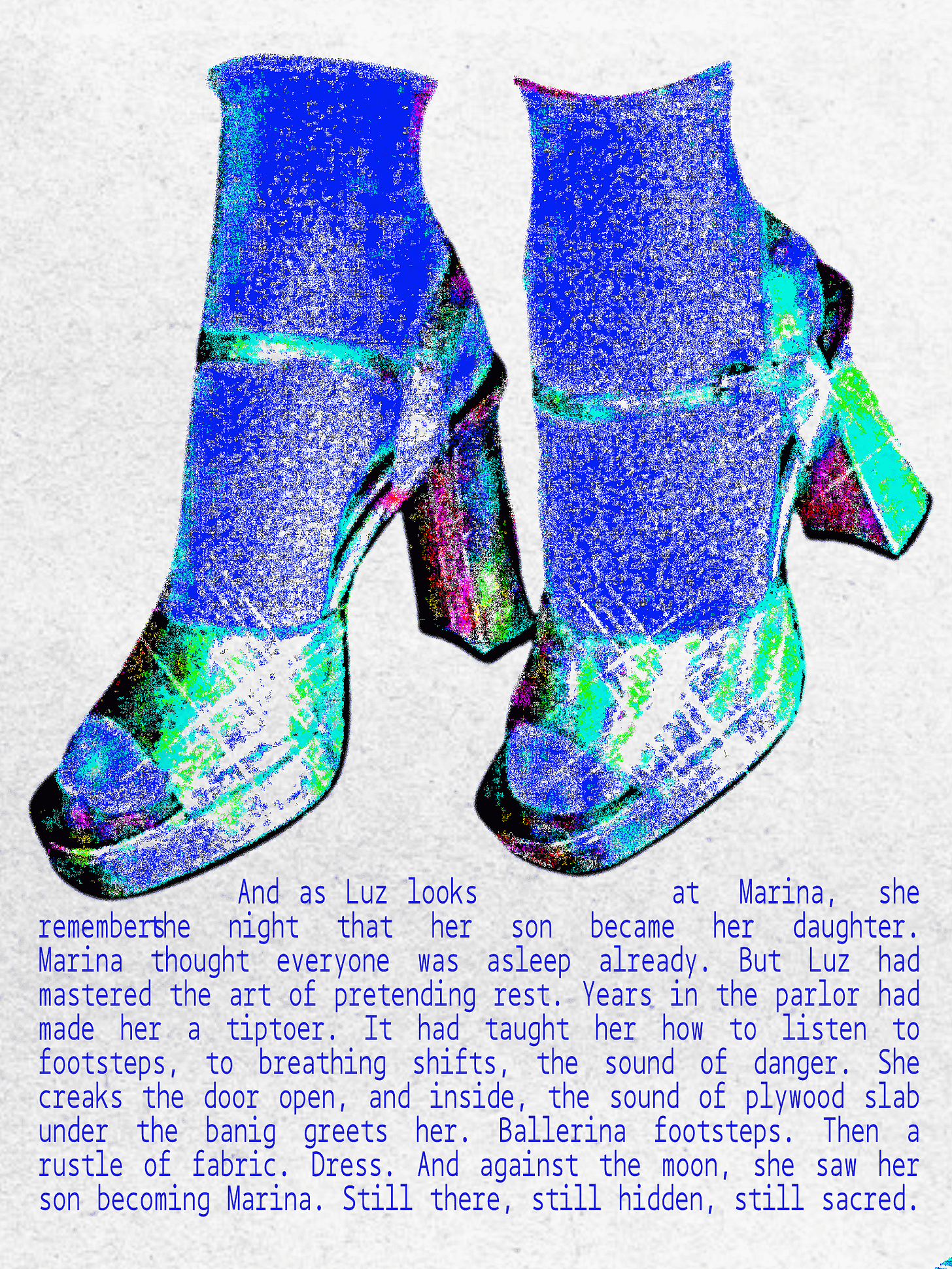

And as Luz looks at Marina, she remembers the night that her son became her daughter.

Marina thought everyone was asleep already. But Luz had mastered the art of pretending rest. Years in the parlor had made her a tiptoer. It had taught her how to listen to footsteps, to breathing shifts, the sound of danger.

She creaks the door open, and inside, the sound of plywood slab under the banig greets her. Ballerina footsteps. Then a rustle of fabric. Dress.

And against the moon, she saw her son becoming Marina. Still there, still hidden, still sacred.

Then the soft clink. The lipstick tube uncapping.

Luz holds her breath. She listens. The pigmented drag on dry lips. The litany of cloth being slid against skin.

When she peeks inside, she sees Marina glowing in the silver of the moonlight. The mirror captures her beauty in the yellow dress, like it was sewn to her soul. The lipstick is wonky, and she giggles to herself.

But it’s perfect.

Luz’s heart stutters. In Marina’s face, Luz sees her mothers.

lampin - traditional Filipino cloth diaper.

lugaw - Filipino rice porridge, often served warm and savory.

Kanal gays – Filipino slang for working-class, loud, street-smart queer people; often drag queens, trans women, or effeminate gay men from impoverished neighborhoods.

chismis - gossip.

barangay - it the smallest administrative unit in the Philippines, similar to a village, neighborhood, or district.

sabungan - cockfighting arena.

Barako - literally a stud rooster; colloquially used to describe macho or hyper-masculine Filipino men.

kumare / kumares - term for close female friends, usually with connotations of godparent relationships.

walis tambo - traditional Filipino broom made of grass.

Miss Pangkalawakan - a playful, campy beauty pageant title in the Philippines, roughly translating to "Miss Universe of Outer Space.

kanto - street corner; colloquial for informal date spots.

noh - Filipino conversational tag equivalent to "right?"

sopas - creamy Filipino macaroni soup, typically with hotdogs and evaporated milk.